In an interview on ESPN last week, Jerry Seinfeld became the latest comedian to decry a culture of political correctness that he says is ruining stand-up. “I don’t play colleges, but I hear a lot of people tell me don’t go near colleges,” Seinfeld told ESPN Radio host Colin Cowherd. “They’re so PC.”

Seinfeld’s sentiments—which sparked predictable backlash and several op-eds by affronted college students—echoed complaints made by Chris Rock in an interview with New York magazine last year. “I stopped playing colleges, and the reason is because they’re way too conservative,” Rock said. “Not in their political views—not like they’re voting Republican—but in their social views and their willingness not to offend anybody.”

The comedian outcry against PC culture—Bill Maher, Jeff Ross, Dave Chappelle and others have publicly empathized with complaints about audience oversensitivity—is predicated on a certain belief about comedy: that it’s an art form worth protecting, even when its practitioners cross traditionally sacrosanct lines. “You don’t want comedy watered down; you want it potent,” Ross said during an appearance on HBO’s Real Time last week. “[Comedians] have a responsibility to shine a light on the darkest aspects of society.” (Incidentally, a Comedy Central special in which Ross “roasted” criminals at a maximum-security Texas jail aired on Saturday.)

Stacked up against the cultural institutions of film, music, literature and art, it’s easy to forget the legacy of comedy, which goes back as far as Ancient Greece—or Lenny Bruce, depending on your perspective. After all, we have roughly 84 reality shows focused on singing, and just one—NBC’s middling Last Comic Standing—devoted to stand-up. That’s as many shows about comedy as there are about dog grooming, diving from extreme heights or dating naked.

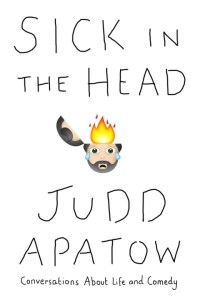

And yet the institution of comedy is aggressively celebrated by a cadre of ardent fans, often the very men and women who grow up to join the industry they worshipped as adolescents. Seated atop this mountain of comedy buffs is a screenwriter and director whose own contributions to humor have earned him plenty of accolades: Judd Apatow. In his first book, Sick in the Head: Conversations About Life and Comedy, released Tuesday, Apatow lays out a multi-decade legacy of comedic inspiration that goes a long way toward addressing why this particular art form has earned its defenders.

Perhaps best known as the director of Knocked Up and The 40-Year-Old Virgin—and more recently as executive producer of HBO’s Girls—Apatow has been, by his own telling, obsessed with comedy for as long as he can remember. As a child, he would circle the names in the TV Guide of every comedian performing that week, and the biggest fight he ever got into with his parents was over a slow-moving family dinner that caused him to miss Steve Martin on The Carol Burnett Show.

As a relatively unpopular 10th grader in the mid-1980s, Apatow began working at his Long Island high school’s radio station, and quickly realized that the station’s call letters (WKWZ 88.5, in Syosset) were enough to score him sit-downs with almost anyone, including soon-to-be comedy legends. Before he was old enough to vote, Apatow interviewed everyone from Jay Leno to Jerry Seinfeld, Weird Al to John Candy, and those interviews were the foundation for a life spent pursuing both comedy and comedians. Sick in the Head is the result of those efforts so far: a weighty compendium of nearly 40 comedian interviews conducted over more than 30 years.

Several of the interviews in Apatow’s book have appeared elsewhere—in magazines, on podcasts, during panels at festivals—but to read them together is to get an uncensored glimpse into the type of person who pursues comedy, and stand-up in particular. Sick in the Head is more than anything an exploration of the kind of drive it takes to devote one’s life to getting laughs, and a look at what that need for validation often says about the person seeking it.

Perhaps surprisingly, there’s a certain darkness to many of the conversations, especially as Apatow grows older and his presence as interviewer becomes less starry-eyed and more introspective. In a talk with Chris Rock, Apatow talks about seeing Richard Pryor backstage in the late ’90s, after Pryor had been confined to a wheelchair because of his multiple sclerosis. “He was doing a bit about a girl walking up to him in his car—he’s flirting with some pretty girl and he’s pissing himself because he’s sick and he can’t control himself,” Apatow tells Rock. “He’s trying to act cool as he pisses his pants.” In a 2014 interview with James L. Brooks (co-creator of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Taxi and The Simpsons), Apatow talks about his parents’ divorce and how a sense of abandonment (“As a kid I thought, No one’s mom leaves. The dad always leaves. Why would she leave?“) drew him to the community of comedians. In a 2005 interview with Harold Ramis (Ghostbusters, Stripes), Ramis refers to Robin Williams, presciently, as “one of the most deeply melancholy people you’ll ever meet.”

Fortunately, there’s also lots of levity. In “Freaks and Geeks Oral History”—Apatow’s 1999 single-season NBC show about high school, F&G was criminally underrated and very ahead of its time—James Franco rather ironically concedes: “I maybe took myself too seriously when I was a young actor.” Chris Rock calls Jerry Seinfeld the Billy Joel of comedians; Garry Shandling explains the genesis of a joke about his inability to get laid. In that same James L. Brooks interview, Apatow jokes about his father’s attempts to get him to stay home from film school to open up a video and CD store.

Apatow: Which is the worst business. It’s like —

Jim: It’s been eradicated from the earth.

Apatow: My dad almost ended my entire career and life.

There’s also a great deal of discussion about the craft, and young Apatow’s earnestness—he is primarily concerned with how to land jokes and gigs—adds humor but also inspires some direct and poignant responses. As Apatow soberly describes his radio program in a 1984 interview with Shandling, “this is the comedy interview program that talks serious about comedy,” and the comedians in Sick in the Head discuss everything from how often they should turn over their acts to how much they should kowtow to different types of crowds.

For fans of stand-up, Sick in the Head is a Bible of sorts, and Apatow’s interviews with Seinfeld, Leno and Rock serve as its de facto gospels. For everyone else, the book is a glimpse into the mind of a comedian—or 38 of them—and the legacy of laughter-inducing honesty they live to protect. Which makes this an extremely relevant book. Because as George Saunders once wrote: “Humor is what happens when we’re told the truth quicker and more directly than we’re used to.”

🏆🏆🏆🏆

TITLE: Sick in the Head: Conversations About Life and Comedy

———————————————

AUTHOR: Judd Apatow

———————————————

PAGES: 489 (in hardcover)

———————————————

ALSO WROTE: n/a (book-wise)

———————————————

SORTA LIKE: WTF with Marc Maron meets Comedians In Cars Getting Coffee

———————————————

FIRST LINE: “How did I start interviewing comedians? That’s a good question. I was always a fan of comedy and…okay, I have been completely obsessed with comedy for about as long as I can remember.”

Republished with permission from Newsweek.com.

sad

Sounds like it’s worth reading for those who’d pursue it, or for the fan of the comics themselves. I would love to interview Bill Burr and Alonzo Bodden. I think they’re comedy masters in their own right.

Thanks for always giving me a great summer reading list!

🙂

ok