A few weeks ago, after handmade pasta and a few too many specialty cocktails, my friends and I got into it over Lena Dunham. Empowered by that special brand of self-righteousness unique to personal opinions about popular things, we loudly and enthusiastically debated the merits of the Dunham Phenomenon—two of us against and one (me) in favor, with a fourth maintaining a wishy-washy neutrality that belied the definitive nature of Dunham’s fame. Indeed, if we’ve learned anything from the post-Girls age, it’s that one is either pro-Lena or against, impressed by her or annoyed, on the same page or reading a different book entirely. There is no Switzerland when it comes to Dunham.

Without even touching on the specifics of her body of work—wry stories of self-involved 20-somethings fumbling their way through adulthood—it would be hard to overstate the size of Lena Dunham’s zeitgeist footprint. She became a household name seemingly overnight, at first because of the critical reception to Girls—both good and bad—and later because of the critical reception to Lena herself: Why so whiny? Why so frequently naked? When clothed, why so much like a toddler? Over time, Dunham’s fame became a self-fulfilling prophecy, and talking about being so over talking about Lena Dunham morphed into the cultural high ground, like hating Uggs or giving up on post-1990 Saturday Night Live.

Even though I like Girls, and am generally impressed with Dunham’s contributions to the irreverent lady essayist genre, I can see why her work grates on people. Girls is unapologetically obsessed with privileged-person minutiae, in an earnest-meets-ironic way that doesn’t have the self-deprecating wit of Broad City or the flippant sexuality of Sex and the City. Dunham, as Hannah, is selfish and babyish, and surrounded by people with equally irksome flaws. I don’t think Lena Dunham much cares whether Girls’ girls are liked or not—in NTKOG she describes the characters in an earlier version of the show as “even more pathetic” than she and her friends were. But if the romantic and professional foibles of upper-middle-class millennials aren’t your cup of tea, then Girls, and by proxy Dunham, maybe aren’t for you.

The same can be said for Not That Kind of Girl, Dunham’s first book, a memoir-meets-essay-collection that earned her a $3.7 million advance. Dedicated to Nora Ephron, NTKOG is reminiscent of Ephron’s own contributions to the comedic essay genre, right down to the cutesy listicles and musings on womanhood. The book has many serious notes—Dunham discusses a dubiously consensual sexual experience, and her struggles with body image and anxiety—but it is also unmistakably her, funny and observant and fearless, though I suspect she’d argue that oversharing isn’t one of her fears.

In the world of the Dunham hype machine, NTKOG is hard to read in a vacuum: One goes into it so prepared to love or hate Lena Dunham’s First Book that I feel almost blasphemous saying I found it simply OK, predictable when focusing on the well-worn territory of Dunham’s parents, sexual history and body issues; bold and insightful when touching on newer topics like her post-fame experiences with powerful men. In some ways the book is like a cross between Ephron’s Wallflower at the Orgy, Chelsea Handler’s My Horizontal Life and Patti Smith’s Just Kids, a comparison that might annoy one or all four of them.

When it comes to the millennial burden—the assumption that everyone under 30 is selfish and entitled and has too many trophies—I think Dunham is held overly accountable, and she is often criticized for writing about the kind of upper-middle-class malaise that earns other authors praise (see: Franzen). When Patti Smith talks in Just Kids about the “scene” of New York City, about hanging out with artsy people in artsy places and making poor life decisions in the name of creative fulfillment, it’s heralded as emblematic of old NYC, and of the way young people in the 60s and 70s stood for something, some determination to realize their artistic potential even if it meant dropping out of school and living in flophouses with money they bummed off friends and relatives. When Dunham writes about taking piddling day jobs so she can mooch off her parents (ironically, grown-up versions of those 60s/70s artists) and pursue her writing career, it’s considered obnoxious.

To be fair, it can be: Despite her talent for storytelling, there are times when Dunham’s anecdotes about coming of age in New York are so patently privileged as to seem like parody. (It’s a fine line that will be familiar to watchers of Girls.) But we can’t have it both ways: We can’t decry post-2000 New York for not incubating writers and filmmakers and artists, and then use one writer’s Manhattan upbringing to discredit her for being “too privileged” to be worthy. To be sure, Dunham’s background and her work are both reminders that we don’t live in a strict meritocracy, that even within the small subsection of people talented enough to be exposed, there are some who will get there easier than others, or will face less resistance on the road to achievement. But living a comfortable life isn’t mutually exclusive with being good at creating whatever it is you love to create.

I think there’s something more insidious still behind Dunham’s most ardent critics—and I refer here not to people who don’t like Girls, or don’t find her interesting or funny; I mean people who hate her with a passion that feels impossibly personal. I read NTKOG while also reading about GamerGate, a debate over gender and ethics in the video game industry that has morphed into a broader argument about sexism. (If you go down that rabbit hole, this is a good place to start), Without getting into the details, GamerGate has shed light on pernicious gender-based aggression festering in a certain group of men who lash out at women online, often viciously and anonymously. It seems that to be a woman with an opinion on the Internet in 2014 is to have unknowingly agreed to be called a stupid cunt by a complete stranger, or to have people “favorite” rape threats against you. One doesn’t need to give too many shits about the portrayal of gender in video games to admit that this is some disturbing stuff, that for all it has enabled, the Internet has also given the worst people an outsized platform to Be The Worst.

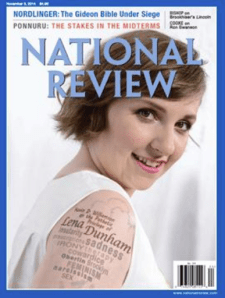

Because Lena Dunham is smart, and forthright about sex, and not a supermodel, she is a natural target for this particular brand of hate, as well as the victim of a more humdrum sexism prevalent outside the lairs of 4chan users. Countless mainstream articles about Dunham reference her body, her promiscuity, her audacity at appearing naked in a show that, let’s be real, is pretty centrally focused on sex. The National Review even put Dunham on their November 3 cover, alongside an article that charges her with cowardice for including the aforementioned semi-consensual sex story in NTKOG. The article, as the Washington Post outlines in a great breakdown, makes typical allusions to Dunham as an overweight slutty liar. “Come on,” author Kevin D. Williamson seems to be saying. “Who would rape Lena Dunham?”

Even if we were to concede Dunham as the least deserving recipient of artistic accolades in the history of time, it seems an unfortunate world in which a woman can’t have her talent judged without her physicality thrown in for good measure. An unfortunate world in which “I don’t like your TV show” is a stepping-stone to “You’re a fat cunt,” a world in which we accept that vitriol as the price of doing business, of becoming popular. I’m not saying people who don’t like Girls are sociopath misogynists; I’m just saying Lena Dunham seems to hit a nerve with the sociopath misogynist set.

In the big picture, anonymity has engendered great things: journalism, whistle-blowing, community-building among the disenfranchised. And in an ideal world, no one would have to worry about a tool like Twitter or Facebook enabling a coterie of assholes to toss out rape threats or misogynist slurs with impunity. No one starring in TV shows or giving lectures on feminism or writing books would have to flee their home for fear of being attacked by someone who simply doesn’t like what they’re creating, or worse, someone who thinks dress size has bearing on the right to create in the first place. To be Lena Dunham is to be on the perpetual front lines of the fight for that ideal world, willingly or unwillingly, and it’s not a job I envy (Golden Globes notwithstanding). Not That Kind of Girl is an unapologetic and earnest addition to the canon of Dunham, a canon as melodramatically controversial as 2008 Lady Gaga, or the final episode of Lost. As a book, NTKOG didn’t blow me away, but I have to admit its author still kind of does.

🏆🏆

TITLE: Not That Kind of Girl

———————————-

AUTHOR: Lena Dunham

———————————-

PAGES: 265 (hardcover)

———————————-

ALSO WROTE: Girls, Tiny Furniture

———————————

SORTA LIKE: Ephron meets Handler meets Crosley

———————————

FIRST LINE: “I am twenty years old and I hate myself.”

Excellent writing.

Yours, not hers.

Nice post

Incredibly well-written, remarkably well-reasoned. Thank you!

I was kind of into Girls for a bit when it first started but honestly could not figure out if I like it or not. I’ll admit at times it was funny because it’s so ridiculous. Eventually it just got annoying though, it’s not that funny and the characters seem to have no redeeming qualities. They seem like the exact people that I avoid in the real world, even as entertainment I have no interest in their petty drama. As for Dunham herself the more I read about her the less I want to know about her.

You write remarkably. Even if one disagrees with the post, your opinion is totally justified. Thank’s for the review. As for Dunham herself, I think the waves she’s made are mainly due to the fact that people around her age in this era can relate to her to a point. The characters in Girls and sometimes herself can be ugly (on the inside) and I believe everyone has at one point felt like an ugly person. It’s nice to see someone is being brutally honest about some personality traits in young people (such as self absorption) without condemnation.

Thanks for such a well-written, intelligent post. It is refreshing to read a review that seems free of personal bias–especially in dealing with an author/filmmaker/actress/everything else who has sparked such a severe polarization of readers and viewers. I’m a fan of your writing, and I look forward to reading more of your reviews!

Reblogged this on The Enthusiast.

Good post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites I stumbleupon every day. It will always be interesting to read content from other authors and use something from other websites.