I really didn’t want to read this book. Or at least I wasn’t supposed to.

Now don’t get me wrong, I love David Foster Wallace. I think he was one of a kind, which is why it pains me every time I decide to read one of his books. Because I know there are a finite number of them; once I’ve read the last one, fin. …I suppose that’s true of many authors, including the classics’, but the circumstance and timing of DFW’s death make it feel relatable, more familiar. In reading his work, I’ve found myself upset that I’ll never know his insight on the current time period–on Obama or Twitter or the Biebs, on Shake Weight, or Watson or 3D movies–because I know his humor, his neurotic thoroughness and unrelenting cynicism, would have made that insight so unique and perfect. Instead I soak up his inner monologues on things like McCain’s 2000 campaign, and pore over his descriptions of a fictional futuristic world eerily like our actual present. And really wish he was still alive to write.

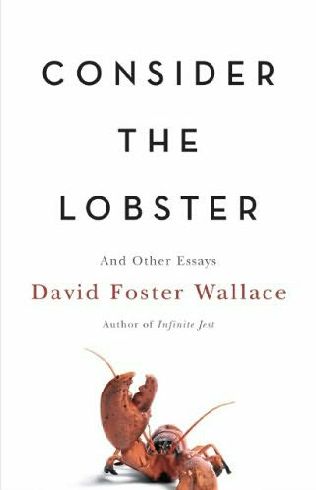

Sigh. Back to the task at hand. So reading any DFW book feels moderately epic. In addition, though I’m a fan of his short stories and novels, I’m partial to his nonfiction books, of which Consider the Lobster is one. Not one, but my last, because I am weak-willed and powerless over a good essay. Also, there’s a lobster on the cover. I can’t be held accountable for that kind of temptation.

Long story short, I’ve decided to drag this one out an extra week, a decision aided by the fact that DFW frequently includes half-page footnotes in footnote-size typeface, and that these footnotes frequently themselves have footnotes in even smaller typeface, so that one feels they’ve read entire pages when they’ve really just managed three lines of a footnote’s footnote. But also, because I want to enjoy it.