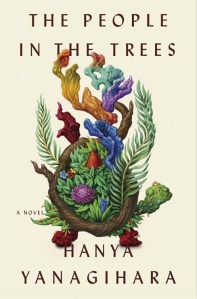

The Amazon reviews on Hanya Yanagihara’s The People in the Trees are a mixed bag, and fairly so: It’s a beautiful, fascinating and imaginative book—that can at times be highly unpleasant to read.

TPITT is, most immediately, an imagined memoir from doctor Norton Perina—the story is loosely based on IRL doctor D. Carleton Gajdusek—who in his 20’s stumbles upon a lost tribe on a remote Micronesian island. A portion of this tribe, who come to be known as “the dreamers,” suffer from a unique affliction that allows their bodies to stop aging while their minds continue to. Centuries old, while physically middle-aged and mentally childlike, the dreamers prove a career-making discovery for Perina, who goes on to become hugely famous and to adopt dozens of the tribe’s offspring. And yet Perina’s memoir is filtered through a second party, Ronald Kuboderia, a former lab assistant (the NYT review, perfectly, describes him as “Smithers to Perina’s Mr. Burns”) who we discover has asked Perina to write said memoir from prison, where Perina is serving time for pedophilia charges. Like I said: unpleasant.

Continue reading “I still haven’t recovered from The People In The Trees”