Tis the season of the beach read, and nothing says beach read like Hitler and slavery.

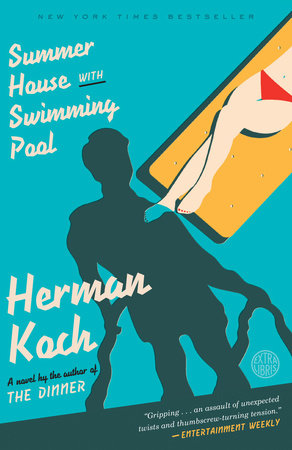

TITLE: Summer House With Swimming Pool

AUTHOR: Herman Koch

PAGES: 387 (in paperback)

ALSO WROTE: The Dinner

SORTA LIKE: Tom Perrotta meets Bret Easton Ellis

FIRST LINE: “I am a doctor.”

Summer House With Swimming Pool is Koch’s second novel translated into English from the original Dutch (I reviewed the first, The Dinner, a few weeks ago). Like The Dinner, SHWSP is a creepy suspenseful family drama involving parents’ actions when it comes to their children.

Doctor Marc Schlosser and his family—wife Caroline and daughters Julia and Lisa—find themselves becoming friends with Marc’s patient, famous actor Ralph Meier, and his family, whom the Schlossers ultimately join on a vacation at the Meier’s summer house. While Marc wiles away his vacay passively loathing Ralph (while half-assedly wooing Judith), both families are suddenly affected by a tragic event that forces them to contend with their true feelings about each other.

Continue reading “Three books to make you uncomfortable”