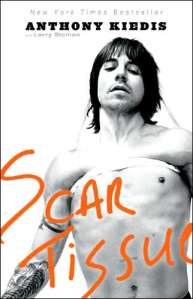

The overwhelming first impression one gets of Anthony Kiedis’s autobiography is: Drug Memoir. Released in 2004, Scar Tissue (co-written with Larry Sloman, who also co-wrote Howard Stern’s Private Parts) did well sales-wise, ultimately hitting No. 1 on the New York Times bestseller list. There’s even an audio version read by Rider Strong (I repeat, Rider Strong). But Kiedis’s whopper of a memoir (~500 pages), was ultimately boiled down into a handful of talking points: band drama, women, drugs. Especially drugs.

That connotation has stayed with STish in the intervening decade, and so what I expected when I first bought my now-battered paperback edition for $1 at Strand circa 2010 was to get mired in a haze of substance abuse, to be taken through a Kerouacian whirlwind of gigs and girls and superstardom. At the very least, I kind of expected Kiedis to be a dick, an “author” because he was convinced of his own magnetism, not because he felt compelled to reflect.

Don’t get me wrong, Scar Tissue is about drugs. Kieidis has at one point or another been a frequent if not daily user of all the usual suspects (marijuana, cocaine, heroin) and, when using, will go for pretty much anything else in a pinch. He smokes his first joint at 11 years old; decades later, his tolerance for opiates is so high that ER doctors have to give him seven shots of morphine, a hospital record. Kiedis’s drug use is hard to read about, and to picture. It’s sad and desperate and nearly destroys his relationships, his career and his life many times. At its heart, Scar Tissue is indeed a drug book.

Continue reading “Dear Anthony Kiedis: Because of Scar Tissue, I forgive you for “Otherside””